Greek researcher Dr Pantelis Natsiavas is on a mission to use technology to rethink the meaning of palliative care for cancer patients, with the help of funding from the EU and 16 healthcare partners from across Europe.

"We are confident that these digital tools work and will improve healthcare services of the future," he said.

Together with his colleagues at the Hellas Centre for Research and Technology in Thessaloniki, Nazziovas is coordinating a ground-breaking initiative (the MyPal project) that has the potential to change the doctor-patient relationship forever - by using digital platforms to improve the quality of care, and therefore the quality of life, of those affected by cancer.

Delivering high-quality medical care is not just about prescribing medicines. Knowledge, as they say, is power; and the way a patient can communicate with their doctor affects their well-being and the ability of doctors, in turn, to provide better care. Everyone deserves a long and healthy life, and patients and their caregivers deserve support.

More than 200 adults and adolescents with cancer in five EU countries (Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Italy and Sweden) participated in clinical trials for just over 2 years using an app called MyPal, a digital tool that allows patients to communicate remotely with their doctors, educate themselves about their disease, report real-time updates about their health and complete questionnaires. Crucially, it gives doctors a more complete picture of a patient's health before seeing them in person, leading to more personalized and targeted care.

"It's a great opportunity," says Naciovas enthusiastically.

"We're still in the infancy of using digital technology in healthcare, but this approach can be used for many chronic diseases, not just cancer. We need to conduct further clinical trials to have hard evidence to present to governments so they can integrate this into health systems," he adds.

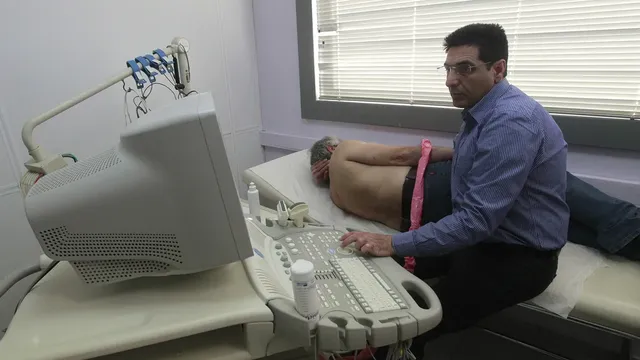

Dr. Thomas Cacciconstantinou has seen the benefits of using the technology first-hand - he treats cancer patients at the G. Papanikolaou in Thessaloniki, one of the two hospitals in Greece where the clinical trials took place. He believes the app's main advantage is that it allows doctors to detect problems with patients before any face-to-face consultation.

It's a complement to usual care, not a replacement for it, explains Catsicconstantinou.

"We usually see patients every three months and only for 10 minutes. But with the app, I can access the information immediately and use it to guide discussions with my patients," he says,

As a repository of medical information, the app accumulates data on each patient and acts as a memory bank, allowing vital patterns to be identified through built-in statistical and analytical features and offering a quick and comprehensive overview of a patient's health status. So it is not just a communication tool. It also addresses geographical imbalances by providing an immediate healthcare solution to patients living in remote locations.

Many of the patients said that communication with their doctors has improved thanks to the trial, reports Cacciconstantinou.

"From my point of view, the specialised app is crucial as it gives a comprehensive picture, with all the information in one place. And instead of adding more work, it actually saves time because much of the assessment is done before you see the patient," he adds.

As a new way for patients to interact with their healthcare teams and for doctors to better serve patients, the sky is the limit in terms of how far it can go. The trials also sought to represent a broader sense of palliative care itself, which people often interpret narrowly as care that people receive shortly before death, but which actually encompasses multiple approaches to optimising support and quality of life for people with serious illnesses.

Naciovas and his colleagues in Thessaloniki are already looking forward to the next steps with their European partners.

"We have proven that these tools have a real application. Now we want to expand the approach," he says.

European health research and innovation is about working together across borders, mutually sharing knowledge and resources and improving our health and care systems together.

Close collaboration between policy makers, researchers, health professionals and patients is a crucial element.

This research is part of the EU's efforts to find new ways to prepare for climate change, protect oceans and waters and fight cancer. Together, EU countries can work more effectively by pooling funding and expertise from around the world, coordinating international efforts and drawing on local know-how. | BGNES

Breaking news

Breaking news

Europe

Europe

Bulgaria

Bulgaria