People write down many things, from epic poems and sacred texts to tax decrees and shopping lists. But these things are of little use to anyone if they can't be read.

Broken tablets, fragile scrolls or coded manuscripts have intrigued scholars for centuries. Many have devoted countless hours to deciphering the writings of the people of the past. Thanks to them, humanity has accumulated a vast knowledge base about writing systems and languages. But some texts still elude our understanding.

Over the past few decades, innovative technologies have developed not only our ability to decipher these ancient scripts, but also to recover information from objects that were once thought too damaged to be understood. Tools such as X-rays, CT scans, and artificial intelligence (AI) are helping today's scientists decipher the contents of seemingly impossible sources.

In the beginning, language scholars in the 18th and 19th centuries had to figure out how ancient writing systems worked. To decipher the writing of an unknown ancient language, they had to do the laborious work of comparing their models with other known languages as well as with written works of the era.

In the late 1890s, Napoleon's troops were stationed in Egypt when they discovered a 4-metre-high piece of black rock known today as the Rosetta Stone. It was once part of a giant stele dating from around 204 BC. On it was inscribed a proclamation of a pharaoh in three different languages, including hieroglyphics that eluded modern understanding in the 18th century. Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion used the other two scripts (Demotic Egyptian and Ancient Greek) and began a decade-long process of trial and error before finally deciphering Ptolemy's hieroglyphs in 1822.

One of mankind's oldest poems came to light in a similar way - with a lot of painstaking work. In the late 19th century, the assyriologist George Smith spent hours at the British Museum reconstructing broken clay tablets covered in cuneiform. He compared the writing with other works from Mesopotamia to uncover the Epic of Gilgamesh, the tale of an ancient hero who embarks on a quest for immortality and learns of the great flood that wiped out humanity.

Fast forward to 2016 and scientists announce they have made a breakthrough in deciphering the Ayn Gedi scroll. Some 1,500 years ago, the animal-skin parchment was in the Holy Ark of a synagogue on the western shore of the Dead Sea. When a fire tore through the community, the city was lost, but the Ark survived. The intense heat from the fire hardened the scroll into a charcoal pipe.

The scroll from Ein Gedi had been carefully preserved for years, but scholars did not know its contents. Because of the heat damage, they thought that unrolling the scroll might turn it to dust. How could they peer into it without damaging the fragile material?

In 2015, a team of scientists figured it out. Using CT scans and specially developed computer software, a virtual copy of the scroll was created. The team could safely unfold this virtual version, allowing them to see the innermost layers and access the hidden text. A year later, the team announced their findings: the scroll is between 1700 and 1800 years old and contains the first two chapters of Leviticus.

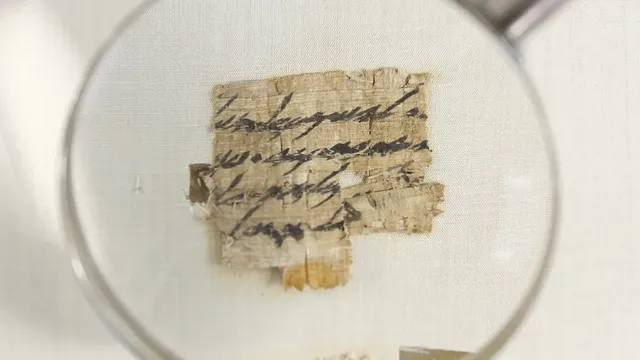

The Dead Sea Scrolls are one of the most interesting and famous archaeological finds of the 20th century. They were first discovered in 1947 in caves near the ancient Jewish settlement of Qumran. Since then, hundreds more have been discovered in the places where they were carefully hidden some 2,000 years ago. Written on papyrus and animal skin parchment, they are among the oldest biblical texts ever found.

Tireless scholars have devoted their lives to studying these precious documents, carefully arranging thousands of fragments to determine their content, provenance and age. The exact authorship of the Dead Sea Scrolls is still hotly debated, but most scholars agree that the documents were written by inhabitants of the Judean Desert between the 2nd century BC and the 2nd century AD.

Advances in genetic research are revealing new information about the scrolls. In 2020, a team of Israeli, Swedish and American researchers tested the ancient DNA of some of the fragments and identified the different animal skins from which the parchment fragments were made. This information gives scientists another data point to help reassemble the myriad pieces of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

After the eruption of Vesuvius volcano in 79 AD, Pompeii and its neighbor Herculaneum were buried by volcanic debris. The two cities have since become living museums that allow visitors to imagine the life of the ancient Romans by the sea. But other treasures, such as the library at Herculaneum, have been slower to reveal themselves.

In a huge villa at Herculaneum, some 1,800 ancient scrolls have been charred by the hot ash of Vesuvius. Hardened into black lumps, the scrolls were discovered in 1752, but no one knew what to do with them. Like the scroll found at Ein Gedi, the Herculaneum scrolls were damaged by the heat and could not be unrolled. But scholars knew that inside lay the tantalising remains of a rich Roman library, perhaps full of works thought lost to time. So the scholars kept them, waiting to discover a way to decipher the contents.

In March 2023, the Vesuvius Challenge announced a competition: use AI to decipher some of the contents of the Herculaneum scrolls. High-resolution CT scans of the 4 scrolls were released, generous prizes were offered, and less than a year later the winners were announced. They had decoded 5% of one scroll, the contents of which were described as ""a 2000 year old blog post on how to enjoy life".

But that's just the beginning: the Vesuvius Challenge has announced another competition for 2024. This time, the top prize will go to whoever can translate 90% of each of the four scrolls scanned.

The Voynich manuscript is not as old as the Dead Sea Scrolls or the Herculaneum library, but its contents are just as enticing. Named after the Polish book dealer who bought it in 1912, it is 240 pages long and filled with colorful illustrations of astrological symbols, undulating plants, and living human figures. Along the vellum pages, dating from the early 15th century, is handwritten text from left to right.

Based on the illustrations alone, scholars believe the book is organized into six sections, divided by subject: botany, astronomy, biology, cosmology, medicine, and cookery. Some believe the book contains science, while others claim it is witchcraft - or perhaps a mixture of both.

For centuries, codebreakers have tinkered with the text, proposing many different theories about its composition, but none of them have held up. Some recent attempts by computer scientists have used AI, but nothing has yet produced solid results.

Today, Voynich's manuscript is preserved in Yale University's rare book collection. It has been digitally scanned and is available online, waiting for the right person or program to uncover its secrets. | BGNES

Breaking news

Breaking news

Europe

Europe

Bulgaria

Bulgaria